Jeff Percy parked his pickup truck beside a lush green field in Coachella, sending a spiral of dust into the morning air.

Behind him, the road led to a reservoir, fenced off by barbed wire. At his feet, a pipe emitted droplets of water to soak the roots of jalapeno pepper plants.

At any time of the day, all Percy needs to do is open an app on his manager’s iPhone to check the precise condition of the soil. Remotely, he can tap a button and release more or less water from his pumping station, so that not a single gallon goes wasted.

“We need to preserve any resource as wisely as we can,” Percy said. “If we don’t take care of the land, it won’t take care of us.”

Now that California is in its fourth year of drought, such technology has become all the more necessary — not just to stay financially solvent, but to meet the demands of the public.

Gov. Jerry Brown’s order for a mandatory 25-percent statewide reduction in potable water use has focused on urban areas and has mostly excluded the agriculture industry. In defending that approach, state water managers have pointed out that farmers in many areas are already being forced to leave fields fallow and cut jobs.

The backlash has been widespread. And it’s been directly primarily at water-intensive crops like almonds and pistachios and alfalfa, which suck up more water than everyone’s showers, toilets, dishwashers and lawns combined.

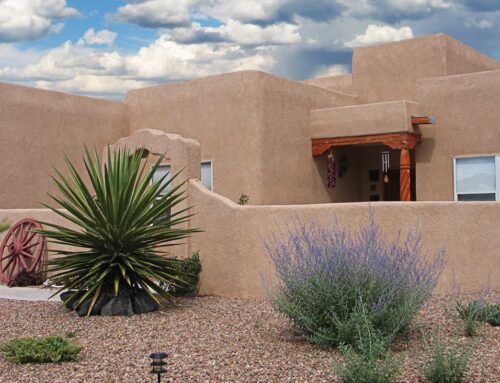

water project april 2015 66.JPG

Jeff Percy, president of Desert Mist Farms in Coachella, checks equipment that monitors soil moisture in a field of jalapeño peppers.

(Photo: Jay Calderon/The Desert Sun)

State water managers say that, historically, about 11 percent of California’s water has gone to urban use, while 49 percent has gone to the environment by flowing through rivers, deltas and wetlands. The remaining 41 percent has benefited the production of food and animal feed, ending in some cases overseas.

Looked at another way, not considering the water that is allowed to flow through rivers and streams for environmental purposes, agriculture consumes about 80 percent of the water that Californians put to use.

In response, farmers like Percy point to their gadgets as proof that they’re already improving the efficiency of their operations — and have been for many years — doing more with less. The situation is far more complex, they contend, than critics realize, but the pressures on supplies will further force the invisible hand of the market toward greater conservation.

They say all this while admitting that the traditional practices of the farm are wasteful.

“The lack of attention to agriculture is a huge problem,” said Jay Famiglietti, a hydrologist and senior water scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “The number one thing that we have to do is to work with agriculture, and that may mean imposing restrictions on agriculture to become more efficient. Yes, they’re making tremendous progress, but much more progress can be made.”

Calls for restrictions on agricultural water use have flared alongside questions about California’s system of water rights, under which farmers with seniority haven’t had to cut back. Such sentiment appears to have had an effect on the governor, who suggested in a recent television interview that every option could be on the table if the drought persists, including the historic system of water rights.

“If things continue at this level,” Brown told ABC, “that’s probably going to be examined.”

-Jesse Marx and Ian James , The Desert Sun